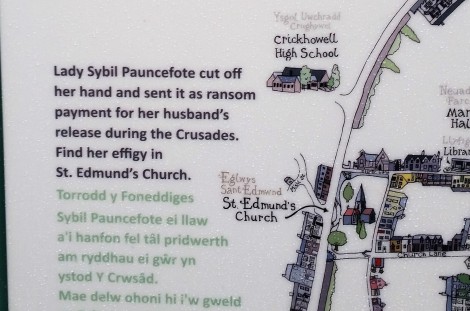

I was walking through Crickhowell recently and paused to look at a tourist information board, not expecting to see anything I didn’t already know. Then I read the following:

‘Lady Sybil Pauncefote cut off her hand and sent it as ransom payment for her husband’s release during the crusades. Find her effigy in St Edmund’s Church.’

Now as statements on information boards go, that’s a corker – it certainly made me read it twice. And it also made me extremely frustrated. They can’t write a statement like that and then just leave it! There are so many questions, aren’t there? For instance:

Why did she cut off her hand to pay a ransom? Was that something that people did then? And was it possible to pay ransom for a person held in the Crusades? Where was he being held? By whom? Whose idea was this ransom – the guy keeping Hubby Pauncefote captive – why would he do that? Or did the suggestion come from Hubby Pauncefote? Or from Lady Sybil herself?

Then the practicalities: once this bizarre demand – or offer – had been made, how did Lady Sybil go about fulfilling the payment? Did she somehow manage to cut off her own hand? Doubtful, I would think. So she must have got someone else to do it for her…who? A relative? One of her husband’s household knights who’d not gone on crusade with him? A local butcher?

Did anyone try to stop her? Was it her right or left hand…and does that matter? And once it had been cut off, who delivered the hand? How did they preserve it so that it didn’t rot on the journey? What proof did they provide that it was actually Lady Sybil’s hand and not that of some poor, tortured peasant girl? And did it work? Did Hubby Pauncefote get home – and did he and Lady Sybil live happily ever after? The unsatisfactory information board.

The unsatisfactory information board.

Well as I’ve said before, I have time on my hands (which was clearly more than Lady Sybil did). So I decided to try to find out. And for once I thought I’d actually try to do this properly – which meant real, honest-to- God research!

(Before reading further, a word of caution: spellings weren’t standardised at this time. Names in particular fell victim to variations – and of course many of these names were of Norman origin, which had then been mangled and abused by Welsh and English tongues for hundreds of years. So, for example, we have Pauncefoot, Pauncefot, Paunceforte and Pauncefote. Also, it was the habit to use a small pool of the same Christian names within a family so that it’s difficult to keep track of which William or Roger or Hugh we’re actually reading about. I’ll spare you too many details of the intensive research and just stick to the more entertaining titbits.)

*

Now then, let’s get the easy bits out of the way: who was Lady Sybil Pauncefote, who was her husband, and where and when did they live? Well, although I feel we’ve all been a little let down by them, the first place I looked was – believe it or not – other information boards around the town. I suppose I felt I wanted to give them a second chance!

The obvious place to start was at the castle and, sure enough, the board there did give a little more information – though nothing like what I really wanted to know. It said:

‘The first castle on the site was timber-built, probably by the Turberville family, after the Norman invasion of the area. It was rebuilt in stone in 1272 by Sir Grimbald Pauncefote, who married a Turberville heiress and was governor of the castle. Effigies of Sir Grimbald and Lady Sybil still lie in the parish church.’

Crickhowell Castle, also later known as Alisby’s Castle after a 14th century governor

Crickhowell Castle, also later known as Alisby’s Castle after a 14th century governor

The rest of the information related to what happened to the castle in the 14th century and later. The parish church in question is St Edmund’s, which is sited a few hundred yards from the castle ruins. St Edmund’s was built by Lady Sybil (I love the way we’re always told that a church, castle, cathedral etc was built by a privileged individual – as though they’d picked up the tools themselves) in the late 13th century. Having drained the tourist boards dry of knowledge I turned to the most useful tool in any 21st century meddler’s armoury: I refer, of course, to the great god Google. Several wearying days minutes(!) later I had tracked down Sybil and Grimbald.

And so, my friends, from the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, National Library of Wales we have this:

TURBERVILLE family of Crickhowell , Brecknock …

… Another HUGH TURBERVILLE was at Crickhowell in 1273…He was the last of the family in the direct line. His daughter Sybil m. Sir Grimbold Paunceforte , whose family succeeded the Turbervilles at Crickhowell .

while the Topographical Dictionary of Wales (British History on line) tells us:

In the reign of Edward I, Sir Hugh (de Turberville), assisted by Sir Grimbald de Pauncefote and Sir Roger de Bredwardine, raised troops in Wales for the king’s service; to the former of these knights Sir Hugh gave his daughter Sybil, with his Brecknock estates, in marriage…

This really interesting book (I kid you not, it’s fascinating) continues with a description of the town and buildings, including the church:

…upon a low altar-tomb, is the mutilated effigy of a knight, in a recumbent posture, cross-legged, and clad in chain mail, having a sword hanging from a belt, and upon the left arm a shield, bearing the device of three lions rampant, the armorial ensign of the Pauncefotes; the inscription is almost entirely defaced, but the tomb is probably that of Sir Grimbald de Pauncefote, husband of the foundress. Lady Sybil herself is supposed to lie interred beneath the opposite arch, where is a low tomb, supporting a recumbent figure of a lady, habited in ancient costume. The interments were made from the outside, as appears from the worked stone facing of the walls at the back of the arches…

So we have documentary evidence that confirms the marriage of Lady Sybil and Sir Grimbald – the importance of this will become clear later – and a description of their effigies in Crickhowell’s church. I managed to haul myself across to St Ed’s to see them for myself, and here they are: Lady Sybil – safely hemmed in by a chair in case she should roll over and fall out…

Lady Sybil – safely hemmed in by a chair in case she should roll over and fall out…

Sir Grimbald – looking a little the worse for wear

Sir Grimbald – looking a little the worse for wear

I couldn’t see any dates (any writing at all, for that matter) around the tombs, for such they are. According to the leaflet at the front of the church, the Pauncefoots are indeed buried beneath their monuments. All things considered I was fairly encouraged up to this point. Back at my laptop I came across an article in the Montreal Daily Witness – the wonders of the internet, eh? The piece was published on 20th March 1889 and included a short biography of Sir Julian Pauncefote, who had just been appointed effective Ambassador to the US. Within this article is the following passage:

There were Pauncefotes in the West of England when the Domesday Book was written. One Sir Grimbald Pauncefote was knighted by Sir Edmund Bohun at the taking of Gloucester Castle during the wars of the barons and obtained from him the lioncello which have constituted the armorial bearings of the family ever since. Sir Grimbald married an heiress in the church of Much Cowarne, Herefordshire. There is still to be seen an effigy of the Pauncefote, who sailed with Prince Edward to Tunis in 1270, and was taken prisoner by the Saracens, and whose wife is supposed to have obtained his release by sending her right hand as a ransom to the infidels. This incident gave rise to the legend of the ‘couped hand’, which is still implicitly believed at Much Cowarne. The Pauncefotes possessed their characteristic motto, ‘Pensez forte’ six centuries at least before Julian Pauncefote was born at Munich sixty one years ago.

*

Now this was good! I’d found a second telling of the story – though I did wonder where ‘Much Cowarne’ was. At this point I had a cup of coffee and a celebratory jammy dodger. Alas, the good times were not meant to last. Things suddenly took a turn for the worse when I found a book called Herefordshire Folk Tales by David Phelps, published in 2009. It is exactly what it claims to be, a collection of folk tales handed down through generations.

The first tale is called ‘A Love Token’ and tells the story of a knight named Grimbald Pauncefote, who lived in the village of Much Cowarne. Sir Grimbald was strong, brave and chivalrous – and married an heiress called Constantia (…hang on, what? who? this isn’t right!), who was the daughter of Sir John Lingen …and it was to her that he gave a fine gold ring, embossed with the three lions rampant that he displayed on his shield.

(No, no, not happy about this…)

After their marriage, Sir Grimbald felt the need to go on crusade. Unfortunately, due to the unfair fighting of the infidels, he was taken prisoner by the Sultan of Tunis – as was Louis, King of France. According to this tale, the Sultan implied that as Sir Grimbald was such a fine figure of a man, he would do nicely as a Eunuch for the Sultan’s harem. The brave Sir Grimbald balked at such a fate and implored the Sultan to send to his wife for a ransom instead. This the Sultan did, and in due course Constantia received a demand for a token to prove that she loved her husband above all other men. Well, the gentle Constantia racked her brain and after a sleepless night, reached a decision as to what her token should be and sent for a surgeon from Gloucester Priory.

A year and a day later – what else? – a courier arrived at the Sultan’s camp carrying a woman’s mummified hand; it was unquestionably Constantia’s hand because it bore the ring with three lions. The story concludes with the happy news that Sir Grimbald was released and made it home to his wife, though he was stooped with age and suffering, his hair whitened. When they died they were buried at Much Cowarne Church, where their effigies can be seen to this day. The Pauncefoot shield in St Edmund’s church, portraying the three lions. Sir Grimbald’s tomb is to the right

The Pauncefoot shield in St Edmund’s church, portraying the three lions. Sir Grimbald’s tomb is to the right

This of course, was not a happy ending as far as I was concerned. As mentioned above, I had found evidence that Sir Grimbald had married Sybil of Crickhowell; the rascals of Much Cowarne had clearly stolen my guys! The whole idea of a woman lopping off her hand for ransom was bizarre enough anyway – it couldn’t surely have happened to two different couples within forty miles of each other, in the same period of time, and with the husband in each case having the same name!

Now, I don’t want to spoil your fun but there’s a poem at the bottom of the page which I have no doubt will have you reaching for a box of tissues. I mention it because this seems a good point to tell you that following this poem in the original anthology, a footnote tells us that the story is a tradition in the family of the aforementioned sir Julian Pauncefote, in whose possession there are ‘various documents attesting its truth’. According to the note, the story harks back to the 13th century, when ‘Grimbaldus de Pauncefort, one of the bravest of the brave knights… married Constantia de Lingaine, a noble lady whose beauty and high-hearted courage made her a fitting mate for the valiant soldier.’ The note then states that papers in the Lambeth Library describe the lady’s effigy in the church of ‘Cowarne Magna, Worcestershire.’

It continues:

“In the vestry is an ancient monument of a woman cut in alabaster without her right hand. This the Inhabitants say was one of the Paunceforts whose husband being taken prisoner by the Infidels, and she being an earnest suitor for his release it would not be granted but by sending her right hand, which she with a Masculine courage caused to be cut off and sent accordingly, & therefore was thus portraced”

“This monument was in existence as late as the last century, but unfortunately is no longer to be seen. The effigy of Sir Grimbald, however is still to be found in the old church of Much Cowarne, as it is now called; and hard by are the ruins of Pauncefort Court, where for many years after the loss of her right hand Lady Constance dispensed her gracious hospitalities with the left.”

You just have to love that last sentence – it’s so Peter Cook and Dudley Moore!

*

In the face of this overwhelming evidence batting for Much Cowarne and Lady Constance, I had no option but to try to find a link between her and the Pauncefoots of Crickhowell – which was fairly easy. It’s difficult to credit these days, but in the Middle Ages – and for a good while later of course – estates were vast. The same family could own acre upon acre, castle after castle. And so although today there doesn’t seem to be a connection between Crickhowell in Brecknockshire and Much Cowarne, the other side of Hereford, back in the 13th century there was no doubt that these holdings belonged to the same family, as shown in the historyofparliamentonline.org. This site provides information about members of the nobility back to 1386 – no earlier, sadly for this particular quest. volume/1386-1421 gives details about ‘Sir John Pauncefoot (1368-c.1445) of Crickhowell Castle, Brec and Hasfield, Glos’.

‘The descent of the Pauncefoot family, which excelled in military engagements in Wales and the marches, especially under Edward I, may be traced from 1199, by which date Sir John’s ancestors were already in possession of Hasfield. Their estates also included the manor of Cowarne and the lordship of Crickhowell (on the borders of Herefordshire and Brecon), and Bentley Pauncefoot in the royal forest of Feckenham in Worcestershire.’

*

So where did this leave us? After over 700 years it’s almost impossible to get to the bottom of such small-scale events because the difficulties with names and records are just too great. When crusades are involved the problems increase; the history of the Crusades is a labyrinthine business. As a case in point, The Montreal Daily Witness claims that Pauncefote sailed to Tunis with Prince Edward in 1270; but by the time Edward arrived at the North African city in November 1270, the French crusaders had already struck a truce with the Emir of Tunis. So…no fighting. Which sort of implies that all is not as reliable as it seems in this particular source…

Then I did what I should have done right at the beginning – I paid a visit to the local library. And there I found, in the reference section (one shelf next to the newspaper table) a small book about St Edmund’s Church, published on behalf of the diocese of Swansea and Brecon. There’s a chapter helpfully titled ‘The Pauncefoot Legend’ (of course there is). According to this, Lady Sybil did indeed forfeit her right hand to her husband’s freedom. And the opening sentence is something of a showstopper:

‘As for the legend of Lady Sybil’s missing hands, it is said that no less than three Pauncefote wives gave their hands as ransom for the Pauncefote men who had been captured by infidels.’

Is it me? What the Hell was wrong with this family? Though at least it appeared that the mystery was about to unravel. I read on.

‘The first was Constance, daughter of Sir John Lingeyn, married in 1251 and wife of Grimbald Pauncefote (grandfather of Sir Grimbald). He was taken prisoner in Tunis and a ‘joint of his wife’ was demanded as his ransom. Constance gave her right hand and he returned home. His tomb is in Much Cowarne Church, Herefordshire. Tradition has it that her effigy lay alongside his and that the stump of her arm was somewhat elevated (Taylor – seventeenth century historian), but her tomb is no longer there.’

Which places this Sir Grimbald nicely in the time-scale for the Seventh Crusade, which was an absolute catastrophe for the crusaders; even Louis IX of France was captured and had to be ransomed – though not by his wife’s hand (and to be fair the Herefordshire Folk Tales gets this bit right). I don’t think this crusade went anywhere near Tunis, though – and it certainly didn’t involve Edward (who was only fifteen years old when it ended), no matter what the Montreal Daily Witness had to say …still, let’s get back to this most riveting of booklets:

‘The second was our Lady Sybil. Her husband was captured by the Muslims during the crusades and there is a ‘Ballad of the Faire Ladye’ which gives in thirty-five verses, and great detail, how, when asked what ransom he could pay he replied ‘I have no lands or gold but I have a wife who would give her right hand for me.’ A palmer was sent to Lady Sybil and she agreed. Certainly her effigy in St Edmund’s is without hands.’

Well there you have it – the stories must be true because the effigies are without hands. Pardon me, but all over the country there are effigies missing bits and pieces. And look at the state of Sir Grimbald! By the way, you may be relieved to know that I haven’t been able to track down the ‘Ballad of Faire Ladye’ because if I had, you would be reading it here. Also a ‘palmer’ was apparently a pilgrim to the Holy Land. Anyhow, the article went on to tell us about the third of these lunatics, which involved a later Pauncefote: Richard of Hasfield. His betrothed, Dorothy Ashfield (or Ashley) of Heythrop was compromised when her fiance was captured by Barbary Pirates. The Sultan’s daughter took a shine to him, so much so that she had him earmarked for a husband until he confidently announced:

‘My lady in England is faithful and true, why she’d give her right hand for me.’

Wow. Poor Dorothy; talk about being dropped in it. The resulting demand duly arrived and according to the ‘Ballad of Hasfield‘:

‘A surgeon from Bristol was most sympathetic

when he explained what it was all about

so he cut off her hand without anaesthetic

and she never so much as cried out’

(I’m pretty glad I can’t find the rest of that little ditty either!)

The Sultan’s daughter, on receipt of the hand, freed the fortunate Richard who returned home to marry Dorothy. She outlived him by nine years and they are buried in Hasfield church.

*

Clearly there isn’t a hope of finding out what really went on all those centuries ago, or get to the nitty-gritty of these weird events. Short of a time-machine how could there be? But just to recap – Constance’s Grimbald was a knight in the Seventh Crusade (1248-1254); they married in 1251 so he probably went after that happy day. He was captured and she sent a hand as ransom. Sybil’s Grimbald (the other Grimbald’s grandson) was a knight in the Ninth Crusade, led by Prince Edward in 1270. He was captured and she sent a hand as ransom; my only problem with this is that according to one source I found, Sybil was apparently born around 1265. I don’t have a huge amount of confidence in this date, though she could certainly have been betrothed at that age. But it makes me wonder how long Grimbald was imprisoned. And from somewhere I now have this horrible vision of a young girl being forcibly held down whilst her hand was ‘removed’ by her husband’s relatives…I hope not. I really hope she was the besotted wife she’s been made out to be.

One last point – the church which Lady Sybil had built as an offering of thanks for the safe return of her husband is dedicated to St Edmund, the only church in Wales to have this name. Why did she pick this particular saint? Again, was it her decision, or was it made for her? Edmund was a king and martyr, killed by the Danes in 869, supposedly defending his Christian faith. Maybe it was felt to be an appropriate choice given that Sir Grimbald had been fighting for his faith on crusade? Or maybe it was felt that she had something in common with Edmund, having made quite a sacrifice herself.

So was Sybil – like Constance before her and Dorothy after – a heroic young woman who chose to subject herself to a horrific mutilation for love and honour? Or was she a victim who had absolutely no say in the matter? Either way, the mind-set of the individuals involved is totally beyond me – but at least I feel I know a tiny bit more than I did when I read that information board! St Edmund’s Church – currently having its roof fixed

St Edmund’s Church – currently having its roof fixed

*

Finally, the treat I promised you. The University of Florida has a digitised copy of a book called Famous Stories and Poems (various authors, published in 1893), which contains such gems as ‘Fluffy’s Easter Joke’ and ‘Aunt Dolly’s two robbers’. As a reward for sticking with me to the end, I present from this scintillating collection:

Sir Grimbald’s Ransom

Like the sands of the sea, like the stars of the sky,

Was the Saracen host as their hoofs thundered by:

The Knights of the Cross like a field of ripe grain

Were mown down before them in windrows of slain.

Sir Grimbald – none braver, none truer than he

Had England discovered ‘twixt moorland and sea –

Sir Grimbald stood up in the ranks of the dead,

And scorned to take flight though his comrades had fled.

“Now God and St George give me grace,” prayed the knight.

“To slay me these infidel dogs in fair fight!

My Constance – Christ keep her! – shall not blush for shame,

Though she die of her grief, when she next hears my name.”

Ten to one were upon him, like hounds on a deer,

But three bit the dust at the point of his spear,

And two tumbled headlong, unhorsed by the shock

Of an onslaught that left him as firm as a rock.

Could Constance have seen him at last overthrown.

No shame for her lord the sweet lady had known;

Nay, even his foes in the desperate strife

Were fain, for such valor, to spare him his life.

In Saracen stronghold they held him instead

Till the Saracen chief set a price on his head:

And the ransom, ah me! That he chose to demand

Was not silver or gold – but a little white hand!

“A little white hand from a woman’s small wrist,”

Quoth he, “is a trifle will hardly be missed –

A trifle that spouse to a husband so bold

Will count it a shame to herself to withhold.”

Ah, woe for Sir Grimbald! In anguish he cried,

“Would God thou hadst slain me! Would God I had died!”

But messengers marched over land, over sea,

To bear Lady Constance the cruel decree.

In her bower they found her, a sweet English rose,

Grown pale with the dread of unspeakable woes;

For she wept through the day, and she waked in the night,

And dreams of her lord filled her soul with affright.

Oh, wan were her cheeks, and her eyes wild with fear,

When the bugle-call rang, and the envoy drew near;

But the rose bloomed again when the errand was said,

And she knew that her hand was the price for his head

“Only that? Nothing more?” Like the sunbeam that lies

On a snowbank, the light that flashed out from her eyes;

Like the laugh of a child, like the song of a bird,

In its eager consent, rang her answering word.

“Draw your sword – here’s a hand will not wince at the stroke;

‘Tis a leaf from a rose, ‘tis a twig from an oak!

Take the ransom so small such a captive to free,

And bring him back quickly – my dear lord! – to me.”

The red lips that smiled and made never a moan

As broadsword cut sharply through sinew and bone,

The bright eyes that sparkled through womanly tears

Are dust of the ages these hundreds of years.

But after two centuries’ roses had bloomed,

They opened the crypt where brave Constance was tombed;

And some that had flouted the story of old

Were fain to confess it was truth that was told.

For the skeleton frame that lay mouldering there,

Half-hid in a tangle of faded gold hair,

Lacked just for completeness the little right hand

That brought her lord home from the Saracen’s land!

Time for coffee, I think.

Pingback: Sybil – My New Shy·

Today, I realized that Grimbald is about my 28-30 great grandfather. I was perusing your account of Grimbald, and was excited. This is great, and I appreciate your research! I understand the connection more than I did this morning. You are gifted, don’t stop… by the way, do you know who is the father of Grimbald, that would be the grandson Grimbald and father, and grandfather Grimbald. Who is the in-between Pauncefort?

Hi Marva, thanks for your kind comments. I’m afraid I don’t know any more about the Pauncefort family tree. So many of them shared the same name and I’m really not sure how reliable any ‘evidence’ is. I’m fascinated to learn that you’re a member of this colourful lot!

You’re welcome. I hope you find everything you want 😊

Just to say I am still following and finding it fascinating!

Hi Anita, nice to hear from you

There must be so many stories that are just waiting to be told – I don’t know if I have the energy or ability but if I come across anything I’ll go for it!

I am researching the Pauncefote family. I am a decendant of Anne Pauncefote of Preston Court, Gloucestershire whose ancestor was yet another Grimbald (born around 1500) of Hasfield married to a Millicent.

Anne was from a “cadet” branch of the family. I am yet to discover how “my” Grimbald is descended from the Crickhowell and Hasfield family.

Can anyone help me?

Hi David I’m not sure what to suggest because this sort of research isn’t within my expertise, as you’ll have realised if you’ve read my post! Are you in the UK? One of the aspects of the family connections that initially tripped me up was the fact that these families owned property which was widely scattered but also (bit of a contradiction) that there were different ideas of distance/boundary etc. So whereas my thinking was initially ‘but Herefordshire’s miles away – and it’s nothing to do with us, it’s in England!” I soon realised I was thinking with a 21st century hat on and needed to understand the interconnections between these Marcher families.

In other words don’t rule anyone out because of geography! And (I’m sure you already know this) the spelling variations don’t help.

Good luck!

Dear Mrs B.

Yes I live in London.You are correct, the Pauncefote family

had properies in several counties.Your research helps to explain why there were at least two ladies–Sybil and Constance who cut off their hands but my cousin in Canada (also a descendant of Anne Pauncefote) feels that we have a stronger candidate in Constance who is the subject of that 1253 marriage contract–a pretty solid primary source.

Many thanks for your lively and informative account.

David

We visited Crickhowell today and read Lady Sybil’s story (or rather lack of story) and was thrilled to find your research. Absolutely loved the page, your fabulous research and humour. Thank you!

Thank you! I was so frustrated when I read that information board that I just had to try and unearth a bit more information. I’m glad you liked it and hope you enjoyed your visit to Crickhowell 🍒

Reblogged this on Giaconda's Blog.

Fantastic bit of history and so well written. My retirement has allowed me to really get into tracing my family history. Turns out John de Pauncefoot, Sheriff of Gloucester, is my great great many times over, grandfather. Not sure I’d do the hand thing though!

Thank you for your comment 🌸 How fascinating that you’re descended from a branch of the family! I agree about the hand donation – it seems an extreme gesture!